Abstract

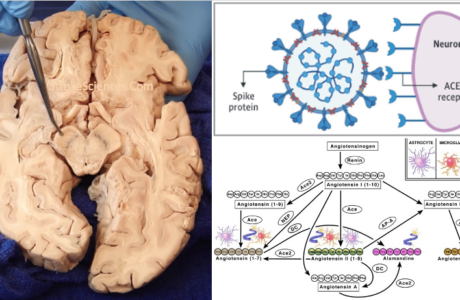

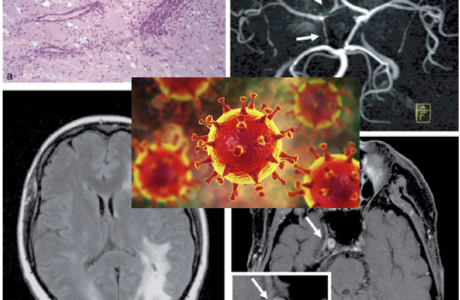

Stroke is a syndrome, an umbrella term for a group of different symptoms based on the location of ischemia, hemorrhage, or inadequate perfusion. In an era where modern medicine relies heavily on sophisticated technology, imaging, laboratory tests, and electrophysiology, the lost art of bedside observation and examination has become a rare skill set in the armamentarium of the modern physician, especially for non-neurologists. This article focuses on the common types and subtypes of stroke and discusses the importance of bedside observations and findings in localizing the lesion.

Contents

1- Bedside Inspection & Observation

1A- Bedside Tests for Cognitive Function

1B- Level of Alertness

1C- Vision and Oculomotor Function

1D- Gait

1E- Motor Function

1F- Somatosensory Function

2- Location-Based Clinical Features

2A- Left Hemisphere Lesions

2B- Right Hemisphere Lesions

2C- Left Posterior Communicating Artery (PCA) Lesions

2D- Right Posterior Communicating Artery (PCA) Lesions

2E- Vertebrobasilar Territory Infarction

2F- Internal Capsule or Basis Pontis Stroke (Pure Motor Stroke)

2G- Thalamic Stroke (Pure Sensory Stroke)

1- Bedside Inspection & Observation

At bedside brain lesions are mainly determined based on patient’s description of their deficits and the findings of your neurological examination8. Although it is gratifying to be able to localize lesions, one ought to remember that location does not change the underlying mechanism of stroke. It is rather important to use neuroimaging modalities in order to determine the pathophysiological basis of a lesion in order to choose the right course of treatment of stroke (ischemia vs. hemorrhage).

1A- Bedside Tests for Cognitive Function

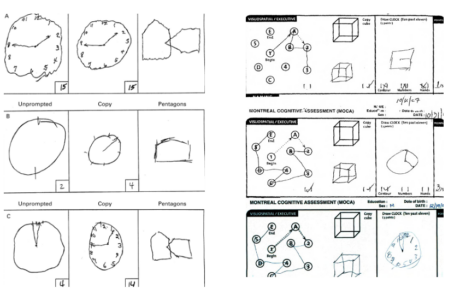

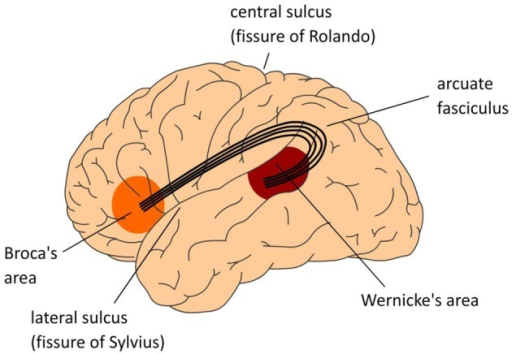

Cognitive tests should be performed especially in patients with right upper or lower extremity weakness as well as right visual field deficits. If you recall, the language centres such as Broca’s area (located in left inferior frontal gyrus) and Wernicke’s area (located in the left posterior superior temporal gyrus lie within the vascular territory of the middle cerebral artery (MCA) which points toward possible right-sided motor and sensory deficits1,3,4. If you are utilizing the NIHSS assessment tool, upon completion of assessment there should be enough information to draw a fairly accurate picture of their state of cognitive function in the absence total loss of consciousness and language barrier5. It is also important to ask the patient to write a few sentences about themselves to differentiate between subtypes of aphasia such as global, expressive, etc. (e.g., conduction aphasia due to lesion in arcuate fasciculus). When patients present with left-sided weakness, looking for the hemispatial neglect could be pursued by asking the patient to draw a clock or a house2,8. In the presence of neglect the patient omits drawing the left side of the image.

In the posterior cerebral artery (PCA) territory, focal lesions could affect memory3,4. Asking the patient to recall a few words or a sentence that you asked them to memorize at the beginning of your examination could be the test of choice for assessing their memory.

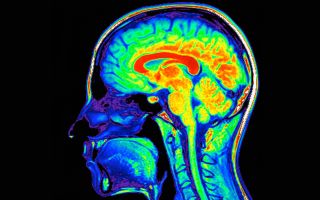

Figure 1- Language centres in the brain (picture credit: Open-i. https://openi.nlm.nih.govAccessed June 1, 2018)

1B- Level of Alertness

One should always suspect a brainstem lesion or an increase in intracranial pressure (ICP) when a decreased level of consciousness is observed5. Determine if the patient is alert, drowsy, or delirious. Does the patient require constant persuasion and cues to stay awake and alert? Family members or nurses who have been at the patient’s bedside longer than you have, could help with these questions10.

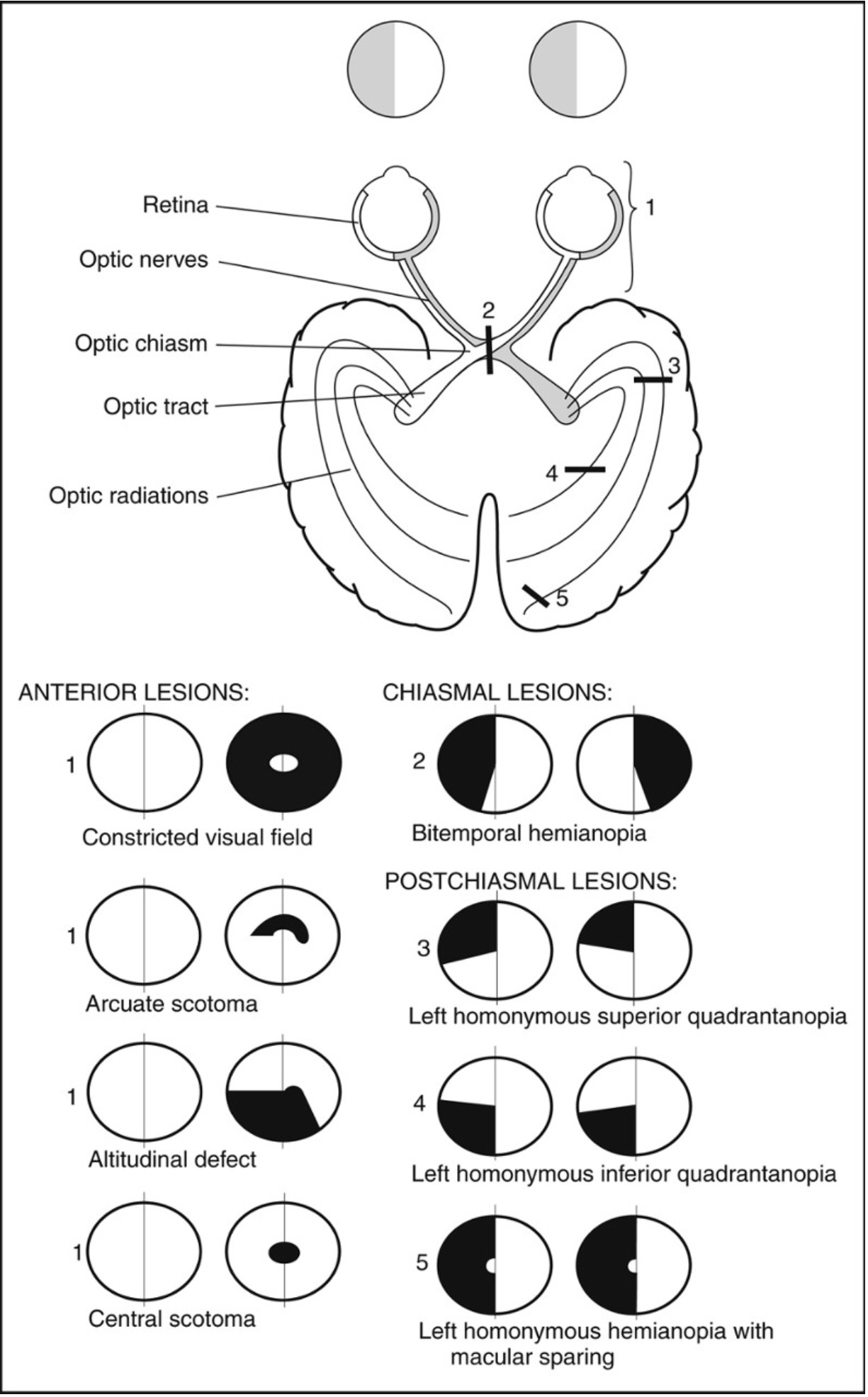

1C- Vision and Oculomotor Function

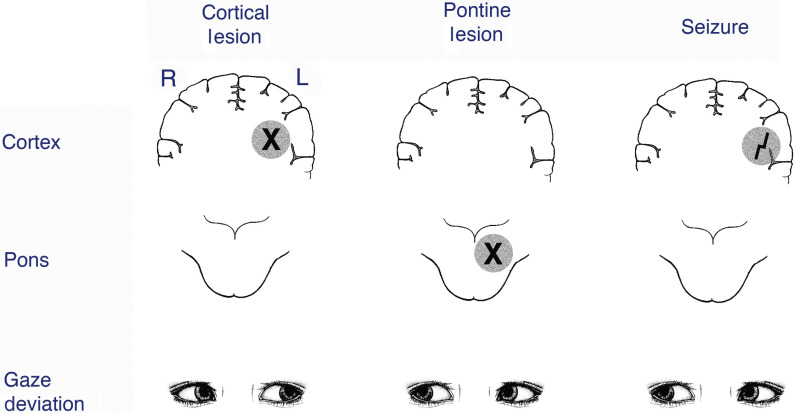

Testing visual and oculomotor function is test that must be performed in almost all neurological disorders. Vision and the movement of the eyes provide important information from cognition to attention. Large posterior cerebral infarcts (occipital lobes) could produce visual disturbances while sparing motor, sensory, and speech functions. Is the patient able to scan objects around the room bilaterally? In acute settings, conjugate gaze paralysis is a common finding on clinical exams1,10. The eyes may deviate to one side, usually toward the side of the lesion (as shown in figure-2), and the patient fails to move both eyes toward the opposite side. This anomaly could be indicative of a frontal or deep hemispheric lesion in the hemisphere opposite to the gaze palsy, or a lesion in the pontine tegmentum on the ipsilateral side as the gaze. On the other hand, vertebrobasilar strokes could cause nystagmus on horizontal or vertical gaze.

Figure 2- Location of lesions and gaze deviation.

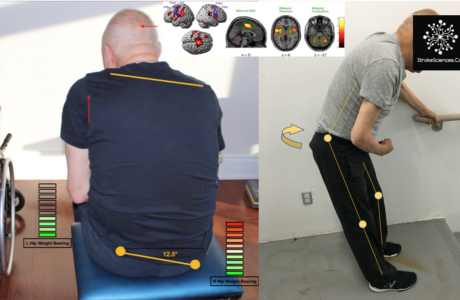

1D- Gait

This one is obviously not always helpful, because most stroke patients cannot walk, and many clinicians are not comfortable to walk a patient with stroke like symptoms. But gait is an extremely important marker in differentiating cerebellar strokes5. These patients often present with normal examination when recumbent or seated but cannot walk. This is a patient population that often is discharged home after initial evaluation but comes back with dismal prognosis3,11.

1E- Motor Function

As mentioned in earlier posts, the NIHSS assessment tool is widely used by neurologists and emergency physicians world-wide. One of its main components is the assessment of motor function. A few important caveats to remember: 1) when testing patients for motor dysfunction, it is important to make sure each limb is tested both proximally and distally1,2,4. As a rule of thumb, you should know that distal weakness is mainly due to central lesions as opposed to the cord or MSK pathologies. 2) After testing for arm drift, toe-object maneuver and coordination, elicit the Babinski sign (other deep tendon reflexes are not important in acute stroke settings).

1F- Somatosensory Function

With cortical lesions patients usually present with marked deficits in domains such as proprioception, object recognition and extinction. After obtaining consent, it is helpful to ask the patient to close their eyes, touch a specific spot on patient’s finger, hand or foot and ask them to touch the exact location (if they could)3.

2- Location-Based Clinical Features

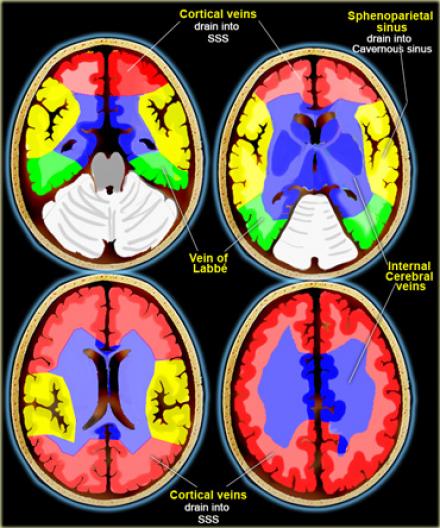

Based on your knowledge of neuroanatomy and clinical observations, you should be able to recognize patterns of deficits in patients and link those deficits to a region known to be involved in those processes12 (Click here for cerebral vascular territories, neuroanatomical features and their symptoms). Here are the main categories for such patterns:

2A- Left Hemisphere Lesions

Lesions in frontal hemispheres due to flow abnormalities in internal carotid artery (ICA), middle cerebral artery (MCA) and anterior cerebral artery (ACA) may present with aphasia, right upper and lower extremities motor and/or sensory weakness or paralysis, right visual field defect, reduced right conjugate gaze, difficulty reading, writing, and calculating2,3.

2B- Right Hemisphere Lesions

In distributive territories of ICA, MCA, and ACA, patients can present with hemispatial neglect (left neglect), difficulty drawing and copying, left visual field defect, motor and sensory weakness or loss in left upper and lower extremities1. Reduced right conjugate gaze. Patient also may present with extinction of the left stimulus of two simultaneously given visual or tactile stimuli3.

2C- Left Posterior Communicating Artery (PCA) Lesions

Left PCA lesions may contribute to the deficits in right visual field, the ability to write remains intact, but reading is affected, difficulty naming visually presented colours and objects, normal repetition of spoken language, and sensory deficits in right upper and/or lower extremities3,8.

2D- Right Posterior Communicating Artery (PCA) Lesions

Deficits in left visual filed, left hemispatial neglect may or may not be present, numbness and sensory deficits in left upper and/or lower extremities10.

Figure 3- Anatomy of the visual pathways and visual field defects following a lesion.

2E- Vertebrobasilar Territory Infarction

This one is not as clear cut as the rest of them. In order to understand the clinical symptoms and presentations of infarctions in vertebrobasilar territory one ought to have a good understanding of the neuroanatomical significance of the posterior fossa strokes, be able to distinguish between vertigo, dizziness and other balance issues and their correlation with stroke3,10. It is often difficult to rule out the central causes of symptoms such as vertigo and ataxia, in future posts this subject will be further discussed in detail, but for now, remember that spinning dizziness, diplopia, weakness or numbness of all four limbs or bilateral regions, crossed motor or sensory findings (e.g., numbness or weakness of one side of the face and the opposite side of the body), ataxia, vomiting, occipital or mastoid headache, neck pain, bilateral blindness or dim vision may all be present3,5,12.

On examination, nystagmus or dysconjugate gaze, gait or limb ataxia, bilateral visual field defects and amnesia may also be present.

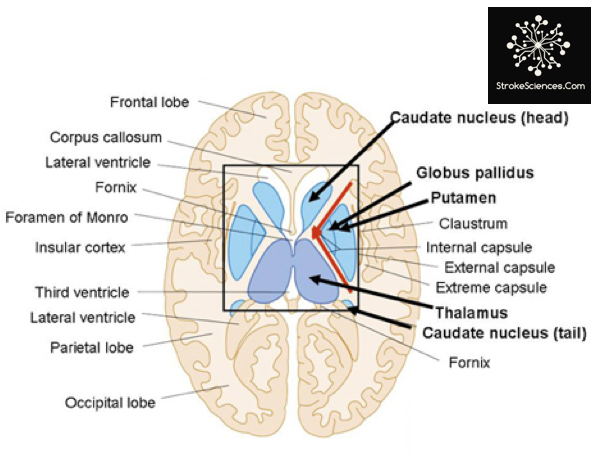

2F- Internal Capsule or Basis Pontis Stroke (Pure Motor Stroke)

Patients with lesions in the base of pons or the internal capsule may present with unilateral facial, upper and/or lower extremities without abnormalities of higher cortical functions (such as language) or sensory and visual dysfunctions4. The level of consciousness in this patient group also is not affected1,12. The hall mark of such strokes is the mixed weakness and incoordination on the same side of the body.

Figure 4- The internal capsule.

2G- Thalamic Stroke (Pure Sensory Stroke)

The last common location of infarcts is the thalamus. Patients in this category often present with unilateral numbness or decreased sensation of face, arm, leg without motor weakness, incoordination, visual or higher cortical function deficits3.

References:

- Adams HP, Lyden P. Assessment of a patient with stroke neurological examination and clinical rating scales. Handb Clin Neurol. 2009;94:971-1009. doi:10.1016/S0072-9752(08)94048-3

- Assir MZK, M Das J. How to Localize Neurologic Lesions by Physical Examination. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2019. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK493159/. Accessed June 6, 2019.

- Caplan LR. Evidence and the Effective Clinical Neurologist: The 2009 H. Houston Merritt Lecture. Arch Neurol. 2011;68(10):1252-1256. doi:10.1001/archneurol.2011.237

- Fink JN, Selim MH, Kumar S, Voetsch B, Fong WC, Caplan LR. Insular Cortex Infarction in Acute Middle Cerebral Artery Territory Stroke: Predictor of Stroke Severity and Vascular Lesion. Arch Neurol. 2005;62(7):1081-1085. doi:10.1001/archneur.62.7.1081

- Fisher CM. The neurological examination of the comatose patient. Acta Neurol Scand. 1969;45(S36):5-56.

- Helleberg BH, Ellekjær H, Rohweder G, Indredavik B. Mechanisms, predictors and clinical impact of early neurological deterioration: the protocol of the Trondheim early neurological deterioration study. BMC Neurol. 2014;14. doi:10.1186/s12883-014-0201-4

- Hui C, Tadi P, Patti L. Ischemic Stroke. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2019. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK499997/. Accessed June 6, 2019.

- Nicholl DJ, Appleton JP. Clinical neurology: why this still matters in the 21st century. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2015;86(2):229-233. doi:10.1136/jnnp-2013-306881

- Ojaghihaghighi S, Vahdati SS, Mikaeilpour A, Ramouz A. Comparison of neurological clinical manifestation in patients with hemorrhagic and ischemic stroke. World J Emerg Med. 2017;8(1):34-38. doi:10.5847/wjem.j.1920-8642.2017.01.006

- Searls DE, Pazdera L, Korbel E, Vysata O, Caplan LR. Symptoms and Signs of Posterior Circulation Ischemia in the New England Medical Center Posterior Circulation Registry. Arch Neurol. 2012;69(3):346-351. doi:10.1001/archneurol.2011.2083

- Spader HS, Grossberg JA, Haas RA, Soares GM. Fundamentals of the Neurologic Examination for Patients Undergoing Central Nervous System Interventional Procedures. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2013;30(3):240-244. doi:10.1055/s-0033-1353476

- Yew KS, Cheng E. Acute Stroke Diagnosis. Am Fam Physician. 2009;80(1):33-40.

Rémy Cohan